Flowering stalks bolt upwards in late July & early August, topped by ball-like buds. Stalks may reach 6-10 feet in height before opening into bright yellow flowers around mid-August.

|

| Silphium terebinthinaceum basal leaves in Durham Co, NC |

Prairie dock develops a significant taproot (see image at Reference # 3), unlike Silphium astericus with which it commonly co-occurs on many Piedmont, North Carolina sites. Dhillion & Friese (4) found that Silphium terebinthinaceum had high levels of mychorrhizal activity (a symbiotic association between the roots and specialized fungi that often confer advantages to the plant in the form of drought resistance, nutrient uptake, etc.).

Very little seems to be known about seed dispersal or pollination, but there are strong suggestions that both are extremely distance limited. Coupled with habitat fragmentation, the result is extreme isolation between remaining populations.

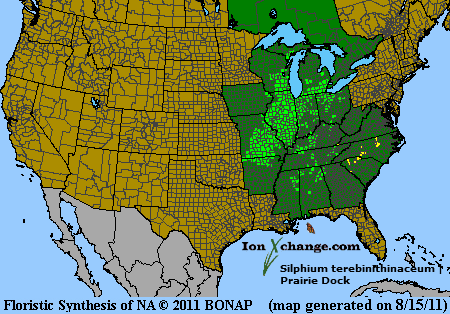

A review of the S. terebinthinaceum range map (see also #5) indicates that North Carolina populations are the easternmost in the nation, significantly disjunct from the heart of the main population centers in Illinois and Missouri (2). What is it doing here in the Piedmont of North Carolina?

|

| Prairie Dock rosettes persisting along roadway in Durham (2006); lack of mowing allowed dense saplings to encroach & suppress most individuals present |

|

| Same site as previous; mowed during growing season (May 2007) |

|

| Same site as previous; note numerous Prairie Dock rosettes (Sept 2007) |

I concur with Schramm (6) "one would think that by now, fire would be universally accepted and vigorously applied in all restoration and management efforts, but fire is being used to conservatively." In addition, he says, "most remnants ... currently need regular burning to regain their original quality", a statement I also agree with in the Piedmont where prairie associated flora remains.

|

| A grove of Prairie Dock flowering (Aug 2014) at site in Durham Co, NC (same site as shown in preceding sequence) |

REFERENCES:

(1) Gleason H.A. and Cronquist A. 1991. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and

Adjacent Canada. 2nd ed. The New York Botanical Garden, The Bronx, New York.

(2) Curtis, J.T. 1959. The Vegetation of Wisconsin. UW Press.

(3) Robertson, K. R. 2007 image. see - http://www.inhs.uiuc.edu/~kenr/prairiephotos/silptere.root1.jpg

(4) Dhillion & Friese; http://images.library.wisc.edu/EcoNatRes/EFacs/NAPC/NAPC13/reference/econatres.napc13.sdhillion.pdf)

(5) http://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=SITE

(6) Hahn P.G. & Orock, J.L. 2014. Effects of Temperature on Seed Viabaility of Six Ozark Glade Herb Species and Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana). American MIdland Naturalist 171: 147-152

(7) Schramm, no date; http://images.library.wisc.edu/EcoNatRes/EFacs/NAPC/NAPC12/reference/econatres.napc12.pschramm2.pdf

No comments:

Post a Comment