|

| Hoary Puccoon (Lithospermum canescens), Halifax County, VA |

|

| Hairy Pucoon (Lithospermum caroliniense), Sussex County, VA |

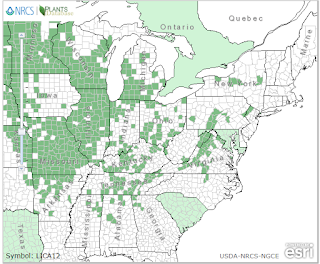

Distribution Maps (County-level)

from https://plants.usda.gov

Hairy Puccoon (Lithospermum caroliniense) (top) has widely disjunct northern and southern populations, with an extreme outlier in southeastern Virginia.

Hoary Puccoon (Lithospermum canescens) (bottom) is strongly centered in the midwestern U.S., gradually dribbling into reasonably adjacent areas of the southeastern U.S

Although apparently closely related "cousins" (Cohen, Cladistics 2011) these species rarely overlap except in parts of the midwestern U.S. L. caroliniense is largely restricted to deep sandy soils. The outlier population in southeastern Virginia is found in historic longleaf pine savanna habitat (see image below), superficially similar to many of the sites for this species in the West Gulf Coastal Plain, East Gulf Coastal Plain of Florida & Alabama, and portions of Florida & South Carolina.

|

| Lithospermum caroliniense in longleaf pine habitat, Sussex Co, VA |

|

| Lithospermum caroliniense in Black Oak sand barren habitat, northwestern Ohio |

|

| Lithospermum canescens in central Piedmont Diabase Woodland, Durham County, NC, with Clematis ochroleuca a Mid-Atlantic endemic |

Both Lithospermum species produce distylous flowers, with two morphological variations potentially present in a given population. These "different forms of flowers on plants of the same species" (to copy the title of Charles Darwin's 1877 work) may ultimately affect the reproductive potential of both the individual and the population as a whole. These flower morphological types, essentially alternate arrangements of the anthers and stigma, can be seen in the the following examples of L. canescens. The uppermost image has "pin" or 'pin-eyed" flowers (stigma elevated above the anthers, which are not visible) while the lowermost has "thrum" flowers (anthers elevated above stigma which is not visible). Theoretically, this pattern should help ensure cross pollination and minimize self-fertilization. McCall (American Journal of Botany, 1996) indicates that little to no seed production occurs when distylous flowers are either self pollinated or crossed with flowers of the same morph.

|

| Pin flowers in Lithospermum canescens, Durham County, NC |

|

| Thrum flowers in Lithospermum canescens, Durham County, NC |

Molano-Flores (Proc. 17th Annual Prairie Conference, 2001) recognized the potential importance of the proportion of flower morphs and examined 17 different L. canescens populations in Illinois. In general, she found many skewed population ratios but also some with equal proportions; importantly she noted differences between "restored" and natural populations.

As suggested above, if one flower morph is disproportionately represented the result may well be low or no seed set. Molano-Flores suggest this problem can be compounded when populations are especially small and/or isolated.

|

| Lithospermum canescens seedling; Granville County, NC (this population supports approximately 50 individuals at last count) |

Given the overall distribution maps (presented above) coupled with localized patterns of habitat fragmentation, it is entirely possible this phenomenon could suggest a threat to remaining populations of both Lithospermum species. Interestingly, Kirster & Levin (Genetics, 1968) inferred that colonies of L. caroliniense are highly inbred and exhibit pronounced gene flow restriction. Levin (American Journal of Botany, 1972) found a higher proportion of thrum flowers and overall low levels of seed production, minimal self-fertility, and minimal compatibility between pins and thrums. Weller (American Journal of Botany, 1980) showed that L. caroliniense has both an inefficient pollination system and intrinsically low fecundity. McCall (American Journal of Botany 1996) found that pins produced somewhat more flowers and fruits than thrums, but that thrums were slightly more common in the population of L. caroliniense she studied.

|

| Monarch feeding on Hoary Puccoon |

How viable are the remaining, isolated populations? Cross pollination appears to be important but Kirster & Levin (Genetics, 1968) found that pollinators (both bumblebees and Lepidopterans) rarely moved more than 10 meters from a given plant!

Given this observation and the apparent low reproduction reported by several authors it is probably especially important that at least one of the species, L. caroliniense, can live as long as suggested by Weller (Ecological Monographs, 1985).

Hmm?