|

Kate's Mountain Clover (Trifolium virginicum) with inflorescence and horizontal leaves in shaded portion of shale barren

Douthat State Park, VA (May 13, 2018) |

Kate's Mountain Clover (

Trifolium virginicum) was first discovered during a plant collecting trip to "southwestern Virginia" by famed botanist J.K Small in 1892. Observed on the rocky slopes of Kate's Mountain, Greenbrier County, West Virginia, Small's published account (1893, Memoirs of the Torrey Botanical Club) indicated this species to be

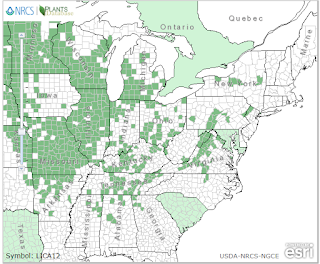

"the most marked new plant collected on the expedition", and distinct from all other eastern American species. Today, we recognize the global range of Kate's Mountain Clover extending across the Valley & Ridge region of VA, WV, MD, and PA as shown on the map below.

|

Trifolium virginicum range,

https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=TRVI3 |

A 1908 botanical monograph on North American Clovers by McDermott lumped Small's Clover with

Trifolium reflexum and suggested that the species was "abundant throughout the Appalachian Mountains". Small's opinion on this treatment was documented by Hunnewell in a brief note entitled, "A new station for three local Appalachian Plants" (Rhodora, 1923). Small was quoted as follows,

"to say that the species is common in the Appalachian Mountains, may be prophecy, but such a statement certainly cannot be backed by good evidence".

Prophetic or not, many botanists have focused their attention on

Trifolium virginicum since then. At one time or another, all Natural Heritage Programs within the natural range have tracked the species. Collectively, the species has been assigned a "G3 or vulnerable" rank by NatureServe. The West Virginia Native Plant Society is justifiably proud of both the plant and its discovery and has adopted the species as their official symbol. Kate's Mountain Clover has also been considered the "flagship species of the shale barrens" (Maryland Botanical Heritage Working Group, 2014).

|

| Shale Barren habitat @ Douthat State Park, VA |

Although Small did not refer to the habitat for his collection as a "shale barren" (the term did not come into common usage until approximately 1911), there are well known shale barrens on Kate's Mountain and some authors have indicated

Trifolium virginicum as a shale barren endemic (Braunschweig, Nilsen & Wiebolt 1999). The species has since been rarely encountered on related habitats, but is still most often associated with shale barrens (see http://vaplantatlas.org/index.php?do=plant&plant=3623).

The typical shale barren habitat is a harsh environment for plant growth. The surface is often unstable with loose rock fragments and minimal soil development & the typically steep slopes tend to shed any litter accumulation down slope where it accumulates at the toe slopes (See images below).

|

| Shale barren fractured rock surface consisting of thousands of "channers" |

|

Toe slope of shale barren/woodland;

green line roughly indicates boundary of litter accumulation |

According to Braunschweig, Nilsen & Wiebolt (1999), surface soil temperatures and high solar irradiance distinguish shale barrens from non-shale barren sites. It has been suggested that air temperatures on the barrens are comparable to the desert regions of North America and several sources indicate soil surface temperatures at shale barrens throughout the mid-Appalachians routinely reach 50-60 degrees Celsius, or 120 degrees Farenheit.

However, such conditions do not prelude seedlings from establishing. I noticed many areas of exposed channery literally carpeted with seedlings (see image below), although I fully expect most of these seedlings to eventually succumb thereby maintaining the relatively open aspect typical of share barrens.

|

| Exposed shale surface with abundant seedlings |

What allows a species like

Trifolium virginicum to adapt to the harsh environmental conditions of shale barrens? Apparently noone really knows! However, Clovers (

Trifolium spp.) are generally known to exhibit "nyctinasty", a fancy word for plant movement caused by a stimulus, and others think of this as "sleep movement." J. W. Harshberger devoted at least 15 years to the study of clovers and devised a contraption to measure the nyctinastic movements of various species (He published his work in the Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 1922). Charles Darwin also studied this phenomenon and wrote an entire book entitled "Power of Movement in Plants" in which he detailed many examples of nyctinasty. A classic example of this movement would be drooping leaves in the evening that open again in the morning, presumably to capture sunlight. However,

Trifolium growing in extreme situations of high irradiance and surface temperature may need to do the opposite. Widening and unfurling leaflets in midday would expose them to potentially dangerous heat levels. Compare the image at the top of this post taken mere moments before the image below. The former plant occurred in a patch of shade and had fully unfurled leaves/leaflets; the plant below shows vertically upright leaves in a sunnier and much hotter location.

|

Kate's Mountain Clover (Trifolium virginicum) with inflorescence and mostly vertical leaves in open shale barren

Douthat State Park, Bath County, VA (May 13, 2018)

I've got to go back to do more field research!

|

| View from shale barren@Douthat State Park |

|